There are many reasons to train animals. It allows pet owners to get along with their furry friends by teaching them basic manners and how to get along nicely with others. Training can also be done for cooperative care, so that you can do husbandry and medical procedures without causing stress to your animal, and to keep yourself safe (think about teaching a horse to stand quietly while doing vaccinations.) You can also train your animal for sport. It’s hugely fun to run an agility course with a dog, or jump a series of obstacles on your horse. I’ve trained various animals (goats, chickens, horses, dogs, fish) for all of these reasons. But although these are worthwhile goals, they’re not why I’ve spent most of my life not just loving animals, but also training them.

I train because it opens up a line of communication with another species. One that goes both ways. The best trainers listen more than they control. They observe small nuances of body language. They’re open to discovering what the animal has to say for themselves and learning what they’re capable of.

In the course of delving into training, I came across the book

Auto Amazon Links: No products found.

Karen began her professional animal training life with marine mammals in the 1960s – at the same time that oceanariums were becoming places not just for entertainment, but also for research into the cognitive and physical capabilities of the animals under their care. In her role as head trainer at Sea Life Park, in Hawaii, she was one of the first to make use of the science of operant learning to train behaviors. But beyond that (which many used simply as a tool), she respected and observed the animals, and was the first to recognize their ability to invent innovative behaviors. The dolphins were creative! That animals had intelligence and original ideas was not something discussed or studied at that time. Through observation, training, and dialog with steno dolphins, Karen was able to communicate with them so that they could show her what they knew. She could tell them (with a cue) show me something new, and they would! When asked, they didn’t do a rote, trained behavior. They clearly demonstrated that they understood the concept of innovation, and they did it! The dolphins would come up with ways of swimming and behaving that they’d never done before. Not in the tank. Not in the wild. All for the sheer joy of being inventive, creative animals (and also for fish.) Karen writes about how she came to that groundbreaking training in this essay which has just been posted on her website. Karen took that training a step further, combined it with rigorous research, and in 1969 published a paper in a scientific journal which opened the door to further research into animal creativity. Read this paper for an historical perspective on how that paper has become the foundation for so much important research since then.

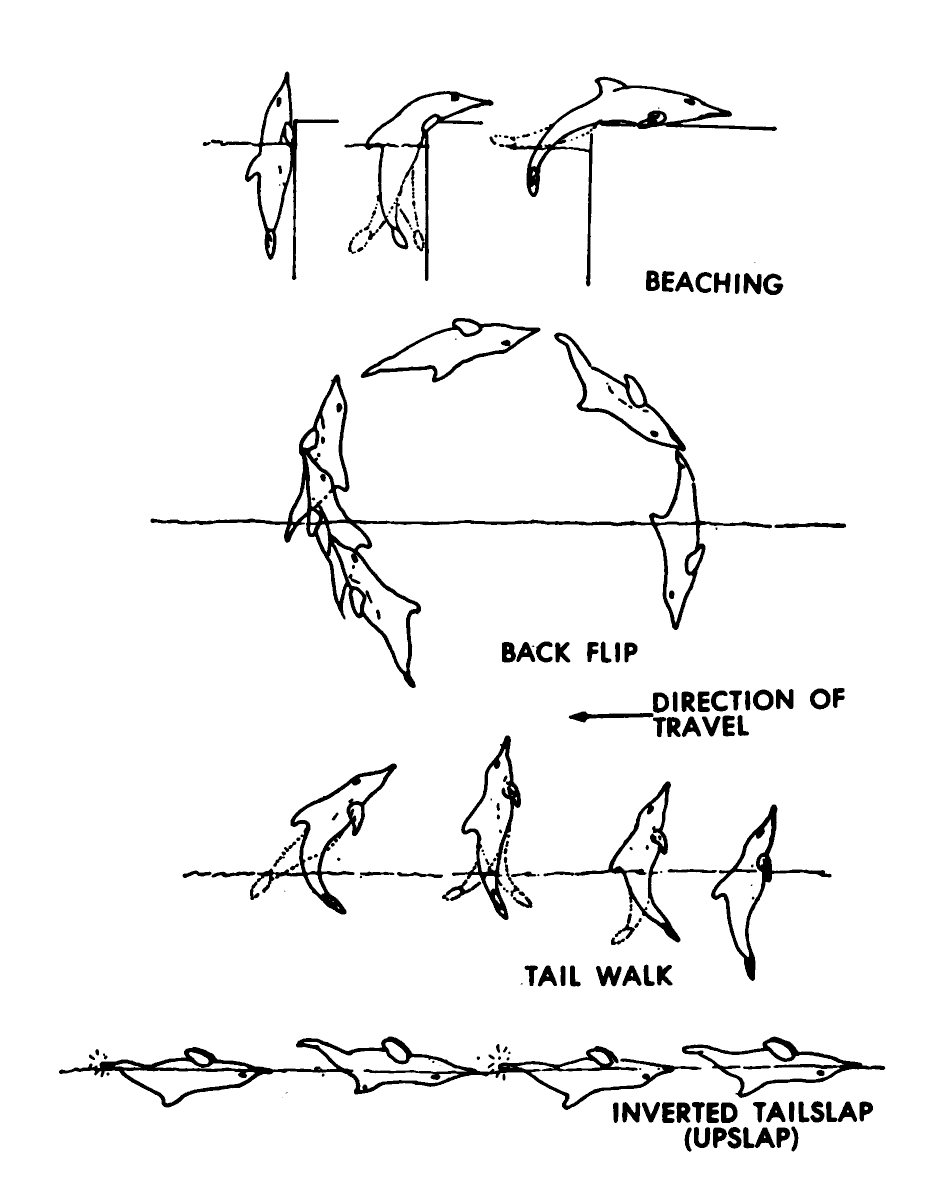

Here’s a diagram from Karen’s original paper from 1969: The creative porpoise: Training for novel behavior.

I haven’t taught my animals the show me something new behavior. But what I’ve learned from Karen about observation and respect for the innate intelligence of animals has enabled me to have a dialog with them. When discussing animal training with me, Karen often uses the word joy. Let’s all put that into our relationships with our animals!

Karen, having an enthusiastic and joyful conversation with my dog, Lily, in 2011.

Karen Pryor, circa 1968

For more about Karen, go to her website, www.KarenWPryor.com, where there is a complete bibliography of her research, articles and books.

I use clicker or positive reinforcement training with my mare at the small private barn where I board her. In the fall and early winter she had to take time off for soundness issues, and I started riding another mare regularly. This other mare, who had always been a well-cared for and beloved but traditionally trained horse, started offering behaviors as soon as I began handling her. She had seen my mare hold my dressage whip for me while I loosened the girth or ran up the stirrups, so she offered to hold the whip. She had seen my mare pick up her the end of her lead rope and hand it to me so she began nosing the lead rope on the ground and trying to figure out how to pick it up. I didn’t treat her because I don’t want her offering “bad” behaviors to the others at the barn, but it was clear to me that she had learned by observation and was choosing to start a conversation about it with me. I’ve never seen her do it with anyone else at the barn.

There are also three young horses I handle regularly, all who know what carrot stretches are. They smell treats on me (and have observed me treat my mare). When I first started handling them (leading them in to groom, putting on and taking off blankets), they mugged me incessantly. I realized they were smelling the pocketful of treats I regularly carry because I have them for my mare. They were desperate for the “carrots.” They would put their noses between their front legs, stretch all the way back to their hip bones, cock their heads and beg. Then they would get frustrated if no treats showed up. I realized I needed to teach them not to mug. It literally took two “clocks” of my mouth for two of them to realize that “head straight forward” is the right answer. Now I can put on a halter and unrug or rug up two of them with one treat at the end (standing still with head forward). The third I started handling later and he’s taken a little longer (he’s younger and has been less handled overall) but he’s figuring it out. I truly believe they picked it up so fast because they watched me play with my little mare. One of the young ones even tried picking up the lead rope for me like the barn mare did.

I think many species are way smarter than we have given them credit for, and I’m glad we humans are beginning to recognize it.

Wonderful examples of animals learning via observation. The intelligence is there, recognizing it is another story. Then, one must not be afraid of that intelligence. Not quashing it, but working with it, as you are doing, is sometimes the most difficult thing.

Fascinating!