I’ve been looking into horses’ eyes lately. Literally and figuratively.

Sight is of utmost importance to the horse, as it is to us. However, although the human eye and the horse eye have similarities, there are also major differences between them. Knowing how your horse uses their sense of sight to perceive their world gives you a window into why they behave the way they do. Understand your horse’s world from their point of view and you’ll be able to interact with them with empathy and effectiveness.

The horse’s eye is one of the largest on the planet. People see that big eye and think that what they see is what we see, except, perhaps, that the horse can see further and with more clarity. That’s not the case at all.

The Streak Of Visual Acuity

Here is one important distinction: humans focus straight ahead, basically in a circle, matching our round pupil. Within that circle, we see detail. The horse has a wide field of vision (more on that later), and their area of sharp focus is called their streak of visual acuity. Take a look a horse’s eye – the pupil is rectangular. Within that pupil is a horizontal line that has the necessary bits of anatomy that allow the horse to focus clearly. Outside of that streak, the world looks rather fuzzy to a horse. Think of it as if the horse is wearing bifocal glasses, but that the magnified strip is in the middle of the glasses, not the bottom. In order for the horse to see an object with clarity, they have to move their head so that what they need in focus lines up with the streak of visual acuity.

Here’s an example of a horse needing to use their visual streak: Tonka and I trailered to a barn to take a lesson. A pet pig lives there. Tonka had never before met a pig. In this photo, Tonka knows that Archie the pig is in front of him, but the visual information is fuzzy. Tonka takes a whiff. Smell is an important sense for horses!

Then Tonka raises and turns his head. Now Archie appears in Tonka’s streak of visual acuity. Tonka gets Archie in focus, and concludes that as weird as this creature is, he’s nothing to worry about.

The visual streak is highly sensitive to changes in brilliance and motion, far more than what we can register with our eyes, which is why your horse can be reactive and startled in situations that to you seems perfectly boring.

The visual streak is also why, although it feels counterintuitive to you, that when your horse is alarmed by something and raises and turns their head, often out of the direction you want to go, it’s best to let them look, rather than to hold on tight and restrict their movement. Once they can clearly see what worries them, they usually settle down. Knowing this allows you to ride a spook so that your horse’s fear quickly deescalates. I’ve written about riding spooks in this blog.

Field Of View

In most situations, horses don’t need to have sharp focus. What they need is to identify moving objects that could spell danger. Horses evolved in grasslands, and so they needed to be able to watch for predators all around them. Their eyes are perfectly suited to this task. Each eye can see a panoramic 200° horizontally, so together, both eyes see 350º. They also have an expansive vertical view – 178º from ground into the sky.

Their world view cannot be captured on camera and shown to you here. You’d have to be in a room with curved walls going both behind you and up above your head and be able to see everything without moving your eyes! It’s hard for us humans, who are forward-focused, to imagine this.

Here’s an image that tries to explain their field of view. What we humans see and pay attention to is the area in the red square. The horse sees that and everything all the way around and behind. When I’m riding my horse to the center of the field, that’s all that I see. But my horse sees the woods on either side (including the house with the swimming pool and the running dog) the barn, the driveway, the horses in the paddocks on both sides, and the hawk overhead. My horse can take all of that in, all at once.

It’s not just out in open spaces that you need to keep their wide field of vision in mind. Let’s say you are heading over this jump. (Photos have been adjusted for the horse’s line of acuity)

This is what you look at.

Your horse sees that jump. But also, everything to the sides, behind and above.

Even though we know that horses have a wide field of view, in our daily dealings with them, it’s easy for us to forget. The other day, I was in Tonka’s small paddock with him. We did some carrot stretches, and I also asked him to back up and to come. I got this face.

It took me a bit to figure out that this grouchy countenance wasn’t directed at me. (It’s awful to see your horse coming at you with such an expression!) The mare next door was out of my field of vision, but not Tonka’s. He was communicating with her. Once I realized this, I moved the training session elsewhere, and Tonka cheerfully did his exercises. So, being aware of what your horse sees and cares about can avert conflict (and hurt feelings!)

Blind Spots

Despite their phenomenal wide-angle view of the world, horses do have blind spots. Blind spots are something that I learned about as a kid. Which is why this advice is common knowledge:

- Never come up directly behind a horse.

- Don’t pat the horse on the forehead because they can’t see the hand reaching for them.

But those words of wisdom are far from the whole story.

Although the horse can’t see what’s directly behind their tail, all they have to do is turn their head slightly to get that piece into their field of view. That said, it’s still very good advice to let your horse know you’re coming up behind them because they can be paying attention to something else, or asleep. I was once kicked over an electric fence because I came up behind a dozing horse.

What I’d heard about the blind spot in the front of the horse was the piece that needed more updating.

Because the eyes are spaced wide apart, there’s a spot in the middle that the horse can’t see. I always assumed that it extended rather far out, even affecting whether they could see a jump in front of them. It doesn’t. This image shows exactly where the blind spots are. Between the eyes. Under the jaw. Above the poll.

Another assumption was that if I held out my hand in front of my horse, that it’d be in his blind spot. Not so. My hand is in his field of view.

However.

Horses have terrible close-up vision! If they were humans, they’d be wearing glasses.

So, this is more likely what he sees when I approach. Whatever I’m holding is a mystery to the horse – until they smell it, touch it with their whiskers, or get a sideways glance.

Which is why it’s still very good advice not to march up to your horse and pat their forehead. No horse likes that.

Instead, say hello. Stroke the neck, scratch the ears, and then you can rub that blind spot between their eyes.

Depth Perception

One of those “facts” that so many of us learned was that horses can see in 3-D in only a small area in front of them, and that in order to have depth perception, a horse has to have both ears facing forward. Not true! Horses have depth perception in about the same field of view as us humans, and their ears can be facing any which way and they can still see in 3-D. However, they don’t have depth perception throughout their entire panoramic field of view. This doesn’t matter much to a horse as it’s only where they’re heading that knowing the terrain matters.

Head Position and Sight

Depth perception is essential when jumping, but as I just mentioned, as long as the jump is in front of you, your horse can see how wide it is. However, there is something more important than depth perception that a horse needs in order to fly safely over an obstacle, and that brings us back to the streak of acuity, and that leads to head position.

You want the horse to be able to see the jump in focus. For that, the jump has to align with the streak of acuity. If a horse were to free-jump, they’d be moving their head as needed to keep the jump in their optimum line of vision.

But what happens when we control the horse’s head? If you tuck their nose in, then what’s in focus is closer and down. The lighter area in this photo illustrates what the horse sees clearly when the head is in this position. The horse does see the jump, but it’s blurry.

This explains why a dressage rider might have issues with their horse spooking at flower boxes in the show ring. If they entered the ring with their horse’s head perpendicular to the ground, then the horse’s focus would be right in front of where they’re going. They won’t see those boxes until they’re almost on top of them. Startling! An easy remedy is to enter the arena on a loose rein. Let the horse look around. Then pick up contact.

In the jumping ring, if the horse is allowed to stretch their head up and out, this is what they can see.

However – see how the tops of the green standards are blacked out? That’s been done to illustrate that that section of the jump is in the blurry zone. No wonder you see horses in the jumper ring wresting the reins from their riders’ hands and raising their heads up. They want to see what they’re jumping!

Here’s a horse who can see clearly what she’s doing. This team looks confident and happy.

Color Vision

Horses evolved to live in wide-open, mostly monotone landscapes. Unlike humans, they don’t need color to determine what is ripe and edible. Instead, horses have the ability to see in scotopic (low light) conditions.

Studying eye anatomy helps us to understand what a horse’s vision is capable of. The human eye has cone photoreceptors. Among other things, cones detect color. Horses have few of those. Horses mostly have rods, which don’t register color, but that do enable the horse to see in scotopic situations. For an animal whose life depends on seeing predators even at night, having rods makes sense.

To the best of current research it’s believed that horses have limited color vision. White is quite bright (luminance!) Yellow and blue are the two colors that horses easily distinguish (although some research indicates that blue lacks clarity and that things that are blue are blurry.) For the horse, orange is the same as yellow. The color that is so important to us – red – blends brown into the background. As does green.

This is what the human sees:

Here is what the horse sees.

Color is so important to us humans that it’s hard to imagine life without it. Color is the thing that pops first into our consciousness and that draws our attention. So even though we know that horses have limited color vision it still surprises us when they don’t care about or notice what we do. That hot pink discarded dog squeaky toy lying in the grass that we think should startle them? Nothing. A dull old green garden hose that is barely noticeable to you in the grass? Yikes! The horse sees it distinctly. Things that are white and without texture, like a plastic fence they’ve seen day in and day out, that happens to be shining in the sun is especially challenging for a horse to identify and focus on – hence, terror!

Unlike that garden hose or the squeaky toy, a flat white surface lacks the textural clues that tells a horse what it is. A horse’s eyes take in more light than ours, and registers brilliance in a more magnified way than ours do. This is why a white fence is often the bugaboo in a course. They’re scarier and easier to misjudge. Colorful jumps might make us nervous – their design looks complicated and confusing to our eyes, but they’re not so disorienting to a horse. It’s the white and shiny fences that are. That’s why, if you take a corner too tight coming into a white gate, you’ll have more of a disaster than if it was a plain natural fence or one painted with red and green diamonds.

A friend kindly let me share this example of what happens at the white fence when the line into it is too tight so the horse hasn’t had a chance to understand what they’re seeing.

So, all of those jokes about terrifying plastic bags and how silly our horses are? If you had their eyesight, that plastic bag would scare you too. It’s shiny, lacks texture, and it moves erratically. Giving the horse a chance to look and understand what they’re seeing takes their anxiety down a notch. Over time, gently exposing them to such things in a non-confrontational way will give them experiences with those objects that will change their attitude from wary to blasé. But you’ll still need to ride a clear line into a shiny white fence!

In Light and Dark

Horses graze up to 18 hours a day, which means that they have to see as well at night as they do during the day. Because of this they have excellent vision in scotopic (low-light) conditions.

Sometimes your horse’s pupil looks bluish-grey. What you’re seeing is the tapetum lucidum, a structure that reflects light back through the photoreceptor layer of the eye so that the horse has a high sensitivity to light, especially light reflecting off of the ground. For an animal that needs to graze at night, and also to see predators, and then move quickly away from them, over uneven terrain, without stumbling, this is a useful adaptation. But there’s a trade-off. We humans don’t have a tapetum lucidum and our night vision is poor. However, we have the ability to adjust our eyes quickly from bright light to dark. Horses do not. It takes horses much longer to see in scotopic conditions, but once they do, they see far more than us.

Walk from sunlight to the interior of a barn.

In five minutes, your eyes have adjusted and this is what you see.

This is what your horse sees. Yes. That dark.

No wonder there are behavior “issues” going into enclosed spaces, or why your horse trips over a lead rope on the aisle’s floor and panics. And why you should always put those saddle racks down when not in use, and why door latches should be smoothly tucked out of the way. The horse can’t see them!

However, in twenty minutes, this is what your horse sees – it’s brighter and in more detail than you can ever perceive. Which is why you won’t notice a sudden movement at the far end of the barn, but your horse will.

Horses need to flee from danger, and so have an innate fear of small, enclosed, dark spaces. Here’s one.

The above photo is how you see the trailer. It doesn’t look so bad. But the photo below is how the horse sees it – the interior is much more of a mystery. Remember that they see in panorama, so there are wide open spaces on both sides. (This photo is also adjusted for their visual acuity and color blindness.) I can understand why the horse, of all of their options in this scene, wouldn’t want to go into that black hole!

This doesn’t mean that loading your horse into the trailer has to be fraught with conflict and pressure. The first thing to do make it brighter inside. If your trailer has them, open the front doors. Here’s the same trailer, viewed with a horse’s vision, with that one easy change. Now the horse can see what they’re getting into.

Many trailers have interior lights. Make use of those, too.

Here’s a horse who is an experienced show horse and usually loads easily. However, she’s never seen this trailer. Note how her body language is tense, she’s stopped at the ramp, and is lowering her head to try to get as much light as possible reflecting off of her tapetum lucidum, and also to get the floor of the trailer into focus using her line of acuity.

We walked her away, opened the doors at the front of the trailer, and had her approach again. She walked right on.

Of course, thoughtful, reward-based training should be part of the picture, too. (I’ve blogged about that. Check the trailering category on the right-hand side of this page.)

When going from shade to sun, a human’s pupil constricts in diameter to let less light in. A horse evolved in a landscape where brightness remains rather constant over stretches of time. They didn’t need to adjust quickly from light to dark, so the horse’s pupil can constrict only a tad. Instead, to protect their pupil from the damaging effects of UV rays, horse eyes have corpora nigra – that’s the raggedy part of the iris that hangs into the pupil and is particularly effective at shading out sunlight from above.

This design is perfect for a grazing animal whose head is usually on the ground and whose eyes scan low across the horizon. The corpora nigra acts as an awning! When a horse’s head is up and in very bright light, the pupil constricts and the corpora nigra partially covers the iris to protect it from being harmed by the sun. It’s like when we try to see through squinted eyes.

The science of sight is complex, and how a horse’s eye transitions between light and dark involves what I’ve mentioned already, and also chemistry. The photoreceptors in the eye go through a chemical change to alter their sensitivity to light. When in bright light, the photoreceptors go through bleaching, and it takes more light to trigger them. When in darkness, they chemically increase their sensitivity to light to enable them to register detail in dark conditions. This chemical change is the major way that the horse adjusts from light to dark, and this is what takes so long. (The reverse, dark to light doesn’t have as long a lag time.)

The takeaway from this is that you might want to try a moonlit ride on your horse. You won’t be able to see where you’re going, but your horse will. On the other end of the (literal) spectrum, when riding out on a wonderfully sunny day, if you head into the shade of the woods, slow down and take your time. Your horse’s eyes can’t be rushed.

How We Know What We Know

To find out how and what a horse sees, I turned to scientists. Some study comparative anatomy – for example, they’ve quantified the number of rods and cones between species. There are those who study the chemistry of sight, which, for example, impacts on how quickly an eye can adjust from light to dark. There are those who use math to measure field of view. Scientists also understand sight by counting nerves, seeing where they’re clustered and what part of the brain they light up. They can also ask the horse! Horses can be trained to let us know whether they can see something (for example, if they can distinguish a line on a card, they touch their nose to a target for a reward.) We know a lot about how eyes function, but not everything. How the brain processes the inputs is a challenge to decipher. What I’ve included here is as up to date as I’ve been able to find. I’m in touch with scientists who are continuing to discover what it’s like to be a horse. (If you’re a scientist in this field, I’d love to hear from you!) In any event, we know enough to challenge some long-held assumptions in the horse world, and to help you see the world from, literally, your horse’s point of view.

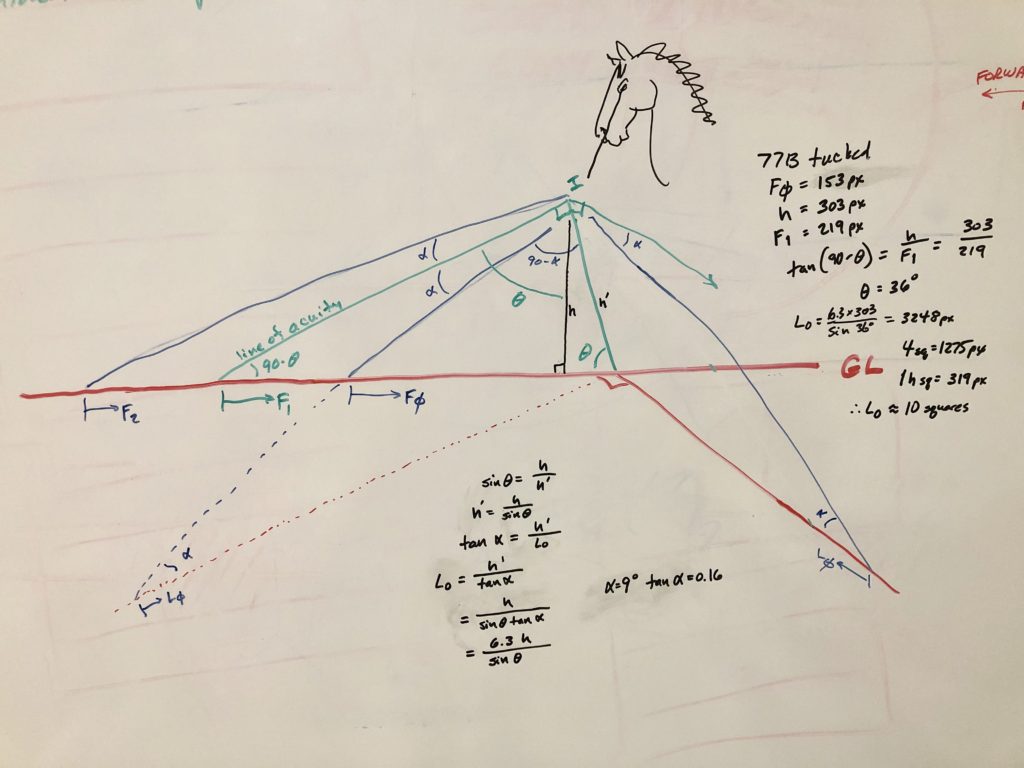

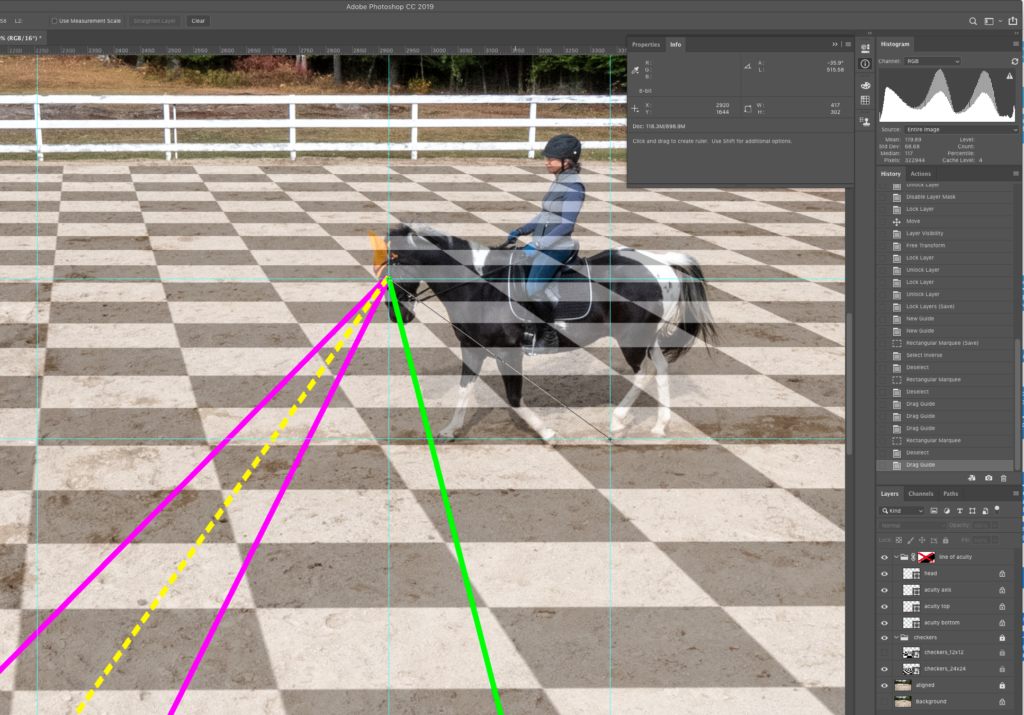

For this blog, I needed illustrations that clearly explained the points that I wanted to make. I enlisted Steve, my husband, to help. Not only is he an MIT grad and total geek (in this household, that’s a compliment and sign of endearment) but he’s an accomplished photographer. He created many of the visuals used in this blog. In doing this project, he quickly discovered why illustrations of horse vision are so rudimentary. Vision is complex, and what a horse sees is far different than what we humans take in, and also not at all like what is recorded on a camera. Scientists have numbers and measurements that detail a horse’s field of vision, their visual acuity and what colors they perceive. But taking those numbers and creating an illustration that a human can understand requires this.

Remember in school when you thought that geometry had no real purpose? These are Steve’s working notes. I contributed the horse head 🙂

Then, once you have that done, you need to take photographs.

Then you need to know how to enter those photos and numbers into Adobe Photoshop. Then you do more manipulations with the computer program.

It was a challenge to do, but worth it, I think!

Thanks also, to my son, Daniel Golson, who put the stylish specs on Tonka.

References

If you want to geek out on the science of horse sight, this article is a great starting point: What Horses and Humans See: A Comparative Review.

Also see this text book Equine Ophthalmology, 3rd Edition, Brian C. Gilger (Editor) especially Chapter 12 “Equine Vision” by Paul E. Miller and Christopher J. Murphy. You can read excerpts here on Google Books. An earlier version of the “Equine Vision” chapter is available here.

Here’s a useful news story from The Horse: Lights Could Help Reduce Horse Stress During Loading, Trailering. You can find the original research here and the presentation (in French) on YouTube.

Research into how equine vision affects jumping safety is ongoing. Here’s one study.

Great read Terry!

Thanks!

Amazing read, thank you for putting it all together 🙂

You’re welcome 🙂

Very interesting and reassuring! I Googled your article to find out about corpora nigra and got so much more!! Thank you!

Thank you for your comment. I’m so pleased to hear that not only is the article showing up in Google searches, but that you found the whole thing interesting!

This is the best (and most thoroughly documented) article I’ve ever found on horse vision. I know how hard it is to find good information on this subject so I appreciate the work and research that went into putting this together. I have shared your article on my business and personal Facebook pages. Thank you!

Thank you! Your comment is very reinforcing to me 🙂

Fascinating article!

Excellent science based information! Trouble at competitions can be the timing. There’s so little time between tests that you may not be able to ride around the entire ring on a loose rein before the judge rings the bell for the start. Suggestions? Also, if warming up indoors and then test riding outdoors, how much time is recommended to allow for adjustments to vision? Thank you so very much for this series – this kind of information can only help horse welfare and human-animal bond!

Going from dark to light isn’t challenging for the eye to adjust to. It’s mostly a momentary thing. So, even if you’re tense from the competing, take a deep breath and do a nice relaxed walk out of the indoor. Give your horse a moment to acclimate and you’ll be fine. I know what you mean about never knowing how much time you have to warm up. I have the opposite problem – Tonka peters out if he goes around the ring too many times. For a spooky horse, if you can get to the venue early and let them watch other horses calmly navigate the ring, that will give them confidence. If you notice other horses all shying at the same place, that’s where you let your horse look. If you’re in a rush, you can try a stretchy trot there.

Terry, thanks for your insights and helpful tips!

Great article now I wonder how when I ride my horse in a fly mask it affects his vision. My horse has uveitis which has been under control for years but I still put a fly mask on during the day to help him with the sunlight.

I don’t have a science-based answer for your question about how much the masks impact vision. However, I do know that for horses with eye conditions, that they are a must. Especially in winter if you are in a snowy area. Snow glare can do as much harm as bright summer sun. It’s great that you’ve kept that uveitis under control. Your horse can do fine with limited vision in turnout – his eye health is so much more important!

This is the most complete article I’ve read yet on how horses see. Thank you!